1990-1991

In 1990, as a member of the Bargaining Committee, Zuss helped formulate ALAA’s strategy during the most contentious contract negotiations since the ten-week strike in 1982.

First, management remained intransigent against demands for more aggressive affirmative action, and refused, even after the contract expired on October 1, 1990, to make any economic offer.

ALAA responded with action modeled on that developed in Brooklyn CDD during the late 1980s, including public rallies, informational pickets, an invasion of the Society’s annual meeting, and disruption of Management’s Christmas party.

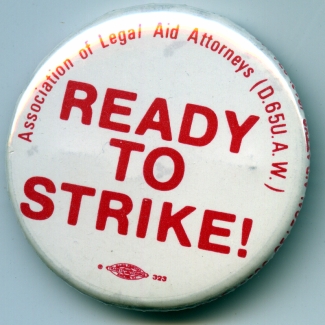

In early October, the union warned that “[i]f management refuses . . . to consider our proposals, they will force us to strike,” a prospect that gained greater prominence on October 4, when members Troy Yancey and Robin Frankel were threatened with contempt in a Manhattan courtroom for wearing “Ready to Strike” buttons. In response, staff attorneys defiantly wore the same buttons to courtrooms across the city.

In December 1990, two months after contract expiration, the Society finally made its economic offer: reduced attorney health benefits and no wage increase — the equivalent of a net three-percent union give-back. Management claimed poverty, but refused to reveal how the Society allocated its $120 million annual budget. On January 29, 1991, union members counterattacked with a one-day strike.

The Society answered by threatening to terminate health coverage for any attorney who refused to authorize payroll deductions toward the cost of insurance premiums. When, in late-February, attorneys voted 515-138 to reject this ultimatum, the Society unilaterally cut benefits.

ALAA was now faced with a dilemma. Its members regarded health give-backs as unacceptable. Most, however, were reluctant to strike. By early spring, therefore, the union implemented “inside” and corporate campaigns that included picketing the law firms of Legal Aid Board officers, mass letter-writing their clients, and threatening to disrupt Legal Aid’s April 24 fund-raising dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

Under this threat, the Society offered to restore essential health benefits, rescind unilateral employee deductions and, for the first time, guarantee existing benefit levels for the life of the contract. Except for a small increase at Step 13, however, salaries were frozen. In other areas, the Society agreed to landmark improvements in job security, equal benefits for same-sex partners, and health and safety.

Although the union had endured, these difficult contract negotiations undermined members’ morale. Deeply concerned about health benefits, salaries and other working conditions, and without a prepared strategy, ALAA had ended up divided about how — or even whether — to resist Management, a schism reflected on the Bargaining Committee. On the other hand, contract negotiations had generated greater membership activism and broad agreement on the need for unified strategy in 1992.

1992

ALAA soon became bogged down in eight months of fruitless mid-contract salary negotiations over pay comparability with assistant district attorneys, causing 150 ALAA and 1199 members to picket Park Row on April 1, 1992.

Frustrated both by 1990 contract negotiations and by the illusory wage reopener, union members told the 1992 Bargaining Committee that — in sharp contrast to the previous settlement — they wanted a significant wage increase, to continue existing health benefits without employee premium contributions or an HMO, and to settle the contract by its October 1 expiration.

To achieve these objectives, the Bargaining Committee proposed a two-part strategy designed to forge broad Staff Attorney consensus.

The first was a “no contract, no work” October 1 strike deadline — backed by development of finances, strike committees and creative strike tactics — to give the union “some muscle at the bargaining table from the moment negotiations begin.”

The second was an “inside strategy” prior to October 1, conducted in alliance with Local 1199 support staff (which had been working without a contract since September 1991), that offered members various ways to build momentum for either an acceptable settlement or a strike.

On June 17, 1992, ALAA members voted to adopt this approach and immediately adjourned to form office-based strike committees.

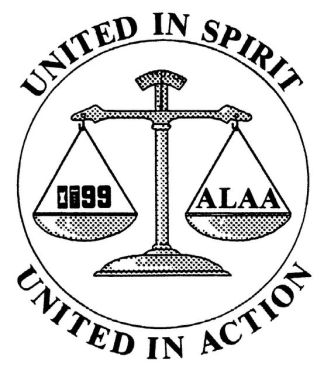

On June 22, 1992, several hundred ALAA, 1199 support staff and Criminal Justice Agency workers (who were also without a contract) picketed the Society’s annual dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, wearing buttons that decided “1199 and ALAA — United in Spirit, United in Action.”

On July 15, the three units held a one-day strike. The strike flyer refuted management’s claim that only the city could provide funds for salary increases, pointing out that “Legal Aid isn’t broke; despite the [city’s] fiscal crisis, its revenues have risen from $101 million to $130 million in just four years and its managers have received a 5-percent wage increase since 1990.”

Once again, the Society played hardball. On August 26, it announced that Staff Attorneys might lose their health benefits altogether unless the contract was settled by October 1.

The union defused this threat by securing agreement of the United Auto Workers (UAW) — with which ALAA later affiliated — to provide emergency health coverage if management cut off attorney benefits. In a final push, all 28 Manhattan CDD attorneys boycotted weekend arraignments on September 12-13, 1992.

On September 19, 200 union members attended demonstrations and 400 turned out on September 23. On September 30, just before the contract expired, reform-oriented Legal Aid President Michael Iovenko convinced the Board to make a new offer, which ALAA ratified by 536-268 on October 2.

For the first time, the Society agreed to expand the concept of “substantial comparability” with salaries for assistant district attorneys through the tenth step, thus generating 6.35 percent in new money, far better than the 1990 contract’s 2.5 percent and superior to NYC municipal union settlements of the same period. The agreement also provided protection from TB, mandatory racial diversity training, and health benefits for lesbian and gay domestic partners.

These positive results, and the membership’s direct role in achieving them, left union morale and credibility far higher than in the previous negotiations.

Incensed, the city’s Office of Management and Budget refused to reimburse Legal Aid for about $2 million of the contract’s cost. It also barred Staff Attorneys from participating in the municipal workers’ health plan, making it necessary for individuals who chose to retain full “indemnity” (non-HMO) coverage to pay heavy health insurance premium contributions.

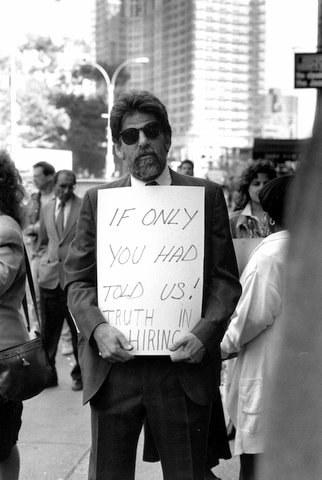

October 1, 1990. Informational picket at Legal Aid HQ, 15 Park Row, Manhattan (first image below). Zuss listening to Bargaining Committee member Azalia Torres (Brooklyn CDD), and speaking at citywide union meeting, 13 Astor Place (second and third images below). Through such democratic debate and action, ALAA members gave the Union real muscle at the bargaining table.

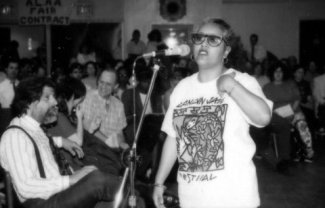

April 21, 1991. Citywide membership debate at 13 Astor Place (below, with Robert Massi). Zuss agreed with the majority that ALAA and 1199 should conduct a joint “inside” strategy to resist management’s demand for givebacks.

Leave a comment